County’s connection to run for president

Clymer’s Horace Greeley was U.S. Grant’s nemesis

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley is the only person with Chautauqua County roots ever to run for president of the United States.

His family lived in Clymer, or more succinctly, Wayne Township, Pa., on a road south of Clymer that delineates New York from Pennsylvania — the state line road. Greeley’s parents, Zac and Mary Woodburn Greeley, were among Clymer’s earliest residents. They moved to the State Line Road in 1826 from Vermont, well before one could easily get from Buffalo.

There were no ways from eastern New York west, either, save for the Erie Canal. But the Greeleys were pioneers. The family made it to North East, Pa., by wagon and then took wagons to Wattsburg, ox carts from the Pennsylvania line between Wattsburg and Clymer, and walked up over the hills to the south and east to the Wayne Township property. A log cabin greeted their arrival. Mary Woodburn Greeley never stopped crying, it was said.

We know all this because Horace’s sister Esther gave his daughters a short book describing the family’s trip from Vermont. Horace Greeley was in his early teens when his family moved to Clymer and joined them after they had moved. He was a son devoted to his parents, and a master editor and publisher who went on to found the nation’s most influential daily newspaper — the New York Tribune. From 1841-1872 his complex personality influenced political thought through the thousands of readers of the Tribune and extensive correspondence with President Lincoln. Greeley was very able and left a puzzling legacy, including conflict with President Ulysses S. Grant and his political followers. That goes directly to the root of this matter — Robert Jackson — more specifically the building where Jackson’s legacy is now preserved in Jamestown, N.Y.

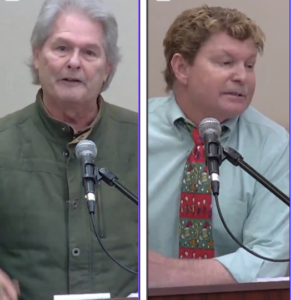

We are Clymer Central School classmates (1956) who began investigating Horace Greeley in Clymer late in life. One was trapped by the Jackson Center’s story on Grant, Chautauqua Institution, Reuben Fenton and Greeley. The other had grown up less than 2 miles to the east of the Greeley property. What else do old folks do but look at the past.

So we wanted to get to the bottom of what was and the story of the earliest immigrations to Chautauqua County. Horace Greeley was involved when the Clymer Cemetery was first properly laid out in 1855 where several Revolutionary War veterans also reside. His parents along with several other members of his immediate family are buried there.

Greeley was a politically active editor that was also one of the founders of the Republican Party. That Party split in the mid-1860s over the corruption said apparent in the administration of President U.S. Grant. Greeley was nominated by those that left the party as a group called Liberal Republicans (yes, Virginia, there once was such a thing), to run for President in 1872. He garnered 40% of the vote, 66 electors and then almost immediately died. So the Jamestown Journal of the day is almost as full of fights over Greeley’s electors as the current papers are full of stories of current losers trying to be called “not losers.” Only three of Greeley’s electors went to Grant in 1872 while the other 63 went to minor candidates.

Grant’s supporters held a campaign event in Clymer in early August 1872 that drew 1,200, and Greeley, himself, campaigned in Corry and Erie in September. Of the campaign it was said it wasn’t apparent if ‘Greeley, was running for President or for the Penitentiary.”

The election of 1872 is how Reuben Fenton, the former governor of New York, got involved with the building that is now the Robert H. Jackson Center. Fenton supported Greeley’s failed run for president.

Greeley was an idealist. As a Liberal Republican, running against Grant, Greeley’s words rang out in speeches as he pressed to normalize relationships with the south:

. “….our country has not been reconciled and regulated, and brought into peace and order….nearly eight years have passed since the (Civil) war ended, and peace and security ought to have been attained much sooner than this.” (Corry, PA, 1872)

Viewpoints and relationships clashed throughout the next decade, bringing controversy to Jamestown via the newly formed Chautauqua Institution, and President U.S. Grant, who was widely supported by Chautauqua County voters, to Alonzo Kent’s home on Fourth Street in Jamestown — not Fenton’s — in August, 1875.

Methodist Bishop John Heyl Vincent had come to Fairpoint on the Lake, founding what is now Chautauqua Institution in 1873. Vincent was itinerant to say the least, and had been the preacher in the Methodist church in Galena, Ill., where he served both Grant’s father, and Grant himself, after the latter returned there following the War with Mexico. On founding Chautauqua with the help of Akron industrialist Lewis Miller, Vincent and the Bishop of the Jamestown region, Thomas Flood, began scheming to bring Grant to his new Chautauqua. Flood delivered a letter of invitation to Grant and a visit actually happened on August 14, 1875. Grant and his entourage came from Washington to Jamestown, arriving for lunch.

Who’s got lunch? Fenton’s home was the logical choice, save he’d supported Greeley, and Grant’s staff wouldn’t allow him to be Grant’s host. So Flood took on the task of finding a place in Jamestown for Grant to eat, and the place chosen was the home of banker Alonzo Kent. The entourage ate and drank (it was Grant after all) at Kent’s house after which a boat parade of 12 took the entourage up the lake to the Institution. One hundred twenty-five years later, the troika Vincent/Flood/Peterson was formed. Greg Peterson gave the room where Grant lunched at the now-Jackson Center the name of the “Grant Room.”

Were it not for Greeley there would have been no reason for President Grant to eat at Kent’s house. Fenton was attracted to Greeley, not Grant, and the current Jackson Center can now claim that small bit of history.

But Greeley wasn’t done with Jackson. Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht was one of 23 indicted Nazis in the infamous International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg at which Robert Jackson was the Chief U.S. Prosecutor. Schacht was born in New York to a German father, and Danish mother. Shortly after he was born, his parents moved back to Germany with young Hjalmar HG Schacht. Horace Greeley von Schacht was one of three Nazis tried at Nuremberg not sent to prison after the trial. And the story distinguished attorney Bernard Melzer told, at the first event of the Robert H. Jackson Center in 2001, was that Schacht was out of the Nazi government when the war began in 1939, and therefore not guilty of war crimes, according to the rules of the trial established by Jackson and others at the London Accord in August 1945.

The Jackson Center owes a great deal to Greeley. That’s not only because one of the indicted Nazis at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg was Horace Greeley Hjalmar von Schacht. Nor is it because Zac Greeley, the son of Horace’s uncle Ben (according to John Q. Barrett) gave Jackson his first hair cut in Spring Creek nor is it because the Clymer cemetery is a veritable treasure trove of early American history. It’s because American history is the study of pioneers and people. Herein, two Clymer natives aim to set that record straight and hope to take our current day Chautauqua County friends on a light-hearted history scavenger hunt for Greeley stories and memorabilia.

Stay tuned for our soon-to-come book on Horace Greeley, his association with Clymer, Chautauqua Institution and Chautauqua County, the stories of his family here, his national influence during the Civil War, and his journalistic influence internationally.